From weak leadership to dangerous and unproven cures, governments around the globe have been touting bad policy solutions to the coronavirus pandemic. Celine Wadhera, a former policy analyst dives into these problematic protocols.

In early 2020, three out of four countries imposed border closures, and half of the global population was living under lockdown measures as the coronavirus spread to nearly every country in the world. By April, however, a number of countries grew frustrated with social distancing and stay at home orders; for some leaders, the economic and political costs of staying at home began to outweigh the human cost of the virus, despite its devastating toll of more than 472,000 deaths globally to date.

The virus first appeared on international leaders’ radar in late December, yet many governments and organizations — particularly the World Health Organization, whose purpose is to promote global health and safety — failed to comprehend its capacity for catastrophe. This was largely due to a failure to properly investigate claims made by the Chinese government that the virus was not transmissible between people, and that its spread was under control. But, as with many global organizations, the WHO relies on its member countries to provide accurate information; it cannot launch investigations, nor can it enforce transparent reporting. So, when it was provided with incomplete or incorrect information from China, what could it have done?

Like many countries around the world, it could have acted more decisively. Countries like New Zealand sprang into action to address the pandemic — closing borders, requiring self-isolation for repatriated citizens, and implementing lockdowns that cancelled events and ordered non-essential services to close. These measures all but eradicated the virus in the country. Other countries, like the U.S. and the U.K., dragged their feet, slowly implementing measures in a haphazard manner, which led to expansive caseloads and death tolls. Madagascar promoted unorthodox treatments for the virus, and Brazil’s leadership tried to ignore it completely. While China didn’t ignore the virus per se, health authorities consistently downplayed its severity and withheld information from domestic and international audiences, enabling a much wider global spread.

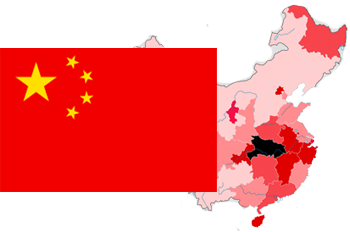

China

Any article on the coronavirus would be remiss without examining the role the Chinese government played in opening pandora’s box. The country’s rigid controls on information and reluctant attitude towards disappointing party leadership significantly contributed to limited speed and transparency when addressing the virus. This hampered domestic and international policy responses, and cost thousands of lives.

In late December, doctors began noticing a pneumonia-like virus in patients that was behaving similarly to SARS, and started alerting their colleagues. Ai Fen, the director of Wuhan Central Hospital’s emergency department, told her superiors that a patient had been infected with a SARS-like virus; the next day, hospital leaders told her that she was “spreading rumours,” and forbade her from saying anything more about the virus, in an effort to keep it under wraps. Ai was shut down, as were many other health care workers who first encountered the virus. On January 2, it was announced on national television that eight doctors who had tried to alert superiors about the virus were punished for “rumour-mongering.” This effectively discouraged others who might have tried to sound the alarm.

In the days that followed, Beijing sent investigators to Wuhan in order to better understand the virus. Local health authorities, however, tried to keep Beijing in the dark. Across Wuhan’s hospitals, the investigators were barred from speaking with doctors in emergency and infectious disease wards, and were given a very narrow purview on what to look for: patients with severe pneumonia who had visited a specific wet market, where the virus is believed to have originated. When asking about infections among medical staff, hospital leadership replied that none existed; however, a recent Chinese CDC study shows that more than six doctors and nurses contracted the virus while the investigators were in Wuhan.

It wasn’t until January 13, when the first case of the virus was reported outside of China, that the Chinese leadership appeared to realize the virus’ pandemic potential. Even then, it wasn’t until a week later that the Chinese public would be made aware of the deadly threat they were facing. On January 14, Ma Xiaowei, the Head of China’s National Health Commission, held a confidential teleconference with provincial health officials, where he provided a grim assessment. “The epidemic situation is still severe and complex, the most severe challenge since SARS in 2003, and is likely to develop into a major public health event,” said a memo from the teleconference, obtained and verified by the Associated Press. It also stated that “clustered cases suggest that human-to-human transmission is possible.”

That same day, the Wuhan Health Commission published the following message: “We have not found proof of human-to-human transmission.” The WHO followed suit, tweeting: “Preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel #coronavirus”.

On January 15, the next day, Li Qun, the head of China’s CDC emergency centre, said on national television: “We have reached the latest understanding that the risk of sustained human-to-human transmission is low,” again downplaying the seriousness of the situation. Three days later, on January 18, a massive banquet was held in Wuhan’s Baibunting district where 40,000 families ate, drank and unknowingly spread the virus.

It wasn’t until January 20 that President Xi Jingping and Zhong Nanshan, a leading Chinese epidemiologist, told the country that the outbreak “must be taken seriously,” admitting that the virus was transmissible between people. Experts estimate that the delay in communicating with the public led to the infection of at least 3,000 people, according to internal documents also obtained by the Associated Press. Even then, it wasn’t until January 23 that lockdown measures were put in place in Wuhan.

Had these measures — the shutdown of public transportation, the closure of airports, the barring of residents from leaving the city — been implemented a week earlier, when experts had a firm grasp on the situation, 67 percent of all cases in China could have been prevented, according to a model simulation developed at the University of Southampton. If measures had been put in place three weeks earlier, the number of infections in China could have been reduced to only five percent of the total caseload, dramatically reducing cases and deaths worldwide. Howard Markel, a public health researcher at the University of Michigan, told nature: “The delay of China to act is probably responsible for this world event.”

This delay was also present in the sequencing of the virus’ genome. Through reporting from the Associated Press, we now know that the genome — a key tool in being able to recognize and respond to emerging pathogens — was fully sequenced in three Chinese labs more than a week before it was shared internationally. This enabled the virus to spread undetected to other countries, and left vaccine and test development a week behind the spread of the virus.

Highly specific diagnostic criteria are also partially to blame for obscuring the severity of the virus. Initially, to be diagnosed with COVID-19, a patient must have had: a fever, radiographic evidence of pneumonia, been treated unsuccessfully with antibiotics, blood cell counts tested, been present in Wuhan (specifically within a wet market), and the virus’ genome sequence confirmed through laboratory tests. These requirements, set by the National Health Commission, were significantly higher than any other infectious disease, and one doctor from Wuhan told The Washington Post that they were “so strict, not a single patient met them.”

These criteria were revised and gradually broadened six times by early March, which enabled wider testing, and amplified China’s caseload. Researchers in the Lancet estimate that if the fifth version of the criteria had been applied in January, there would have been 232,000 confirmed cases in China by early May — more than four times the official count of 55,508.

United States

As lockdown measures were being implemented in Wuhan, the WHO was busy labelling the virus a Public Health Emergency of International concern, and called on all countries to “prepare for containment, including active surveillance, early detection, isolation and case management, contact tracing and the prevention of onward spread.” As is now abundantly clear, many countries did not heed this warning. A glaring example this failure is America.

It wasn’t until February 25 that the American Center for Disease Control (CDC) told the country to prepare for an outbreak; by this point there were more than 80,000 cases of the virus worldwide, including at least 53 cases and two deaths in the U.S. Just over two weeks later, when there were at least 1,666 coronavirus cases and 41 deaths in the U.S., President Donald Trump declared “two very big words”: a national emergency.

Throughout the pandemic, Trump has consistently led the American public astray. In mid-January he said, in a CNBC interview, that the virus was “totally under control” and that things were “going to be just fine.” He reiterated these messages on January 30, adding “we think it’s going to have a very good ending for us…that I can assure you.” By this point, the virus was already present in America and the WHO had labelled the virus a Public Health Emergency of International concern, warning all countries to “prepare for containment, including active surveillance, early detection, isolation and case management, and the prevention of onward spread.” Trump’s public reassurances were nothing more than fluff that provided a false sense of security to millions of Americans; if they were going to be “just fine,” there was no need to worry about containment and self-isolation, the virus wasn’t going to spread there.

But, once it was clear that the virus was spreading in the U.S., Trump pivoted towards bad science. On March 9 he tweeted: “So last year 37,000 Americans died from the common Flu. It averages between 27,000 and 70,000 per year. Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of CoronaVirus with 22 deaths. Think about that!”

Not only was this misleading, but dangerous; the 37,000 cited for flu-related deaths is not of deaths directly attributable to the flu — which in 2019 was 7,428 across America — but a CDC estimate for the total number of people who die from flu-related illness on an annual basis, many of whom are not actually tested for the flu. COVID-19 deaths are only counted in the official toll if the patient has received a positive result in a lab test, almost certainly guaranteeing more deaths than the official toll indicates. Moreover, Dr. Anthony Fauci, a member of the president’s coronavirus task force and the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has consistently and publicly disagreed with Trump’s flu comparison. “The flu has a mortality of 0.1 percent. This has a mortality rate of 10 times that,” he said at a hearing on Capitol Hill on March 11. Throughout the pandemic it has been clear Trump’s assertions were wrong and dangerous, yet he chose to ignore these warnings at nearly every turn, endangering American lives.

Testing was also an issue; on March 10, when Trump told the nation: “Anybody that needs a test can get a test,” fewer than 10,000 Americans had been tested — 0.003 percent of the population. One reason testing was delayed was the methodology; rather than using the WHO-approved test, the U.S. chose to develop their own test, which was sent to laboratories across the country but delivered inconclusive results, causing a three-week delay in widespread testing. Had the U.S. decided to use the WHO test kit in early March, following the WHO’s advice to engage in active surveillance and early detection, contact tracing could have been implemented, and the spread of the virus could have been dramatically reduced.

Despite allegedly testing negative for the virus throughout the pandemic, Trump’s statements around the virus turned from bad to worse when he began to endorse potentially dangerous measures to combat the virus. In March, he began promoting anti-malarial drugs as a treatment for COVID-19.

“Now, a drug called chloroquine — and some people would add to it ‘hydroxy’. Hydroxychloroquine …it’s been around for a long time, and it’s very powerful. But the nice part is, it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if it — if things don’t go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody.”

Except that it might. Although both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are used to treat malaria, they have different chemical compounds; chloroquine predates its prefixed substitute, is more toxic, and risks severe side effects including vision problems, irregular heart rhythms, and low-blood sugar, which, if untreated, could be fatal. A small-scale study in Brazil demonstrated this; patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were put on differing doses of chloroquine as a means of treatment; eleven patients died as a result.

Later in March, Trump expanded this recommendation, saying that hydroxychloroquine should be taken with azithromycin — an antibiotic used to treat strep throat, pneumonia, and chlamydia — in order to “have a real chance to be one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine.” However, an expert panel at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommended against this combination, due to an increased risk of sudden cardiac death. A game changer indeed. The panel also recommended against the use of chloroquine because of its toxicity, and cautioned against using hydroxychloroquine outside of hospitals or clinical trials. Despite these recommendations, Trump continued touting the so-called therapies, even alleging that he was taking hydroxychloroquine himself.

Departing again from the president’s advice, Dr. Fauci repeatedly said there was no conclusive evidence to support using hydroxychloroquine, and when asked on March 24, whether it should be used as a treatment for COVID-19, he said unequivocally: “The answer is no.” Rick Bright, the doctor in charge of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority at the Department of Health and Human Services also disagreed with promoting the drug, writing that the government should instead have invested in “safe and scientifically vetted solutions, and not in drugs, vaccines and other technologies that lack scientific merit”; rather than considering this advice, the administration dismissed Dr. Bright from his position.

In late April, when the U.S. had the highest caseload in the world, and more than 50,000 deaths, Trump presented some more problematic policies. At a press briefing where William N. Bryan, the Head of Science at the Department of Homeland Security, said that sunlight, bleach and alcohol could kill the virus on surfaces in as little as 30 seconds; Trump chimed in:

“Supposing we hit the body with a tremendous — whether ultraviolet or just very powerful light…supposing you brought the light inside of the body, which you can do either through the skin or in some other way…And then I see the disinfectant where it knocks it [coronavirus] out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside, or almost a cleaning? Because you see it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs.”

It would indeed do a tremendous number on the lungs. “Inhaling chlorine bleach would be absolutely the worst thing for the lungs,” Dr. John Balmes, a pulmonologist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, told Bloomberg News. “Not even a low dilution of bleach or isopropyl alcohol is safe. It’s a totally ridiculous concept.” Even Reckitt Benckiser Plc, the maker of Lysol and Dettol released a statement on April 24, saying: “Under no circumstance should our disinfectant products be administered into the human body.”

The day after Trump made his statements on bleach and sunlight, he claimed he was “asking a question sarcastically of reporters” to see what would happen, acting as if his words had no consequences. Yet, within the 24 hours between those “questions” and his follow-up statement, calls to poison control centers across the country skyrocketed; many of them reported the ingestion of chemical products.

Moreover, the CDC published a report in June revealing that calls to poison control centres had increased at least 20 percent since 2019, and 39 percent of survey respondents admitted to high-risk activities, including washing produce in bleach, inhaling household cleaners, and applying these products to their skin — activities which could easily result in deaths.

Trump also made questionable calls around public health policies. On March 16, he announced “15 Days to Slow the Spread,” which was ultimately followed by another “30 Days to Slow the Spread.” These announcements included measures such as working from home, hand washing, self-isolation, and protection for high-risk individuals. Although these measures were absolutely good ideas, and reduced the virus’ ability to spread within the country, researchers at Columbia University estimate that if they had been implemented one week earlier, by which point nearly 1,000 Americans had been infected, 36,000 lives could have been saved. Two weeks earlier and 54,000 lives could have been saved.

Elements of international pandemic response were also dismantled under the Trump administration, particularly in China. For 30 years, the American CDC has had an office in Beijing, but since 2017 the staff count has shrunk by 70 percent to just 14 people, losing medical epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists. Similarly, the National Science Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development, which both monitored emerging diseases, shuttered their Chinese offices.

Furthermore, USAID has for years funded PREDICT, a global initiative that identified viruses with pandemic potential, and trained staff in foreign laboratories. Over the past decade, this initiative identified 1,200 viruses, including 160 novel coronaviruses. Funding for the program ceased in September 2019, months before COVID-19 was first detected in Wuhan. Had the program continued, one must wonder, would there have been a pandemic at all?

While it would be impossible to cover all of the missteps and miscalculations made in America’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic, bad decisions are evident in terms of caseload and death toll; at the time of publication, the U.S. has the highest death toll in the world at more than 123,000, and the highest caseload at 2.4 million.

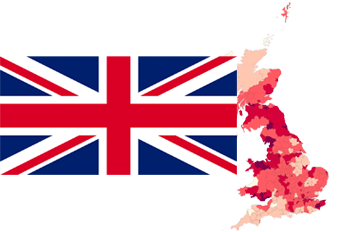

United Kingdom

Another country that personifies poor pandemic policies is the United Kingdom. The country currently has the highest caseload and death toll across Europe — the fifth highest in the world — and the country’s prime minister fell ill with the virus, after downplaying its severity and boasting about shaking hands with hospitalized coronavirus patients weeks earlier.

The U.K.’s biggest policy sins stem from a sluggishness to recognize and respond to the threat posed by COVID-19; this has been described as “the greatest science policy failure for a generation,” by the Lancet’s editor in chief, Richard Horton, in his new book The Covid-19 Catastrophe. This foot-dragging left the country wildly underprepared for the outbreak it was about to experience.

Although it was clear at the end of January that the virus was spreading internationally, the U.K. did little to prepare, save for organizing flights to repatriate citizens from Wuhan. On January 24, the same day that the Lancet, the world’s oldest peer-reviewed medical journal, released a report stating that the lethal potential of coronavirus was comparable to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, which killed 228,000 Brits and more than 50 million people worldwide, Health Secretary Matt Hancock told reporters that the risk the coronavirus posed to the UK public was “low,” despite the fact that it was already circulating internationally.

On February 3, Prime Minister Boris Johnson opted not to implement measures to restrict movement, saying: “Coronavirus will trigger a panic and a desire for market segregation that go beyond what is medically rational to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage.” He added that lockdown measures, including border closures, business closures, and the prevention of free movement, in other countries were “autarkic” and “bizarre.” By the end of the month, there had been more than 37,000 cases of the virus worldwide and 23 cases in the U.K., but still, few measures were put in place. Moreover, the prime minister missed five consecutive COBRA meetings on coronavirus responses while he spent nearly two weeks at his country retreat. Perhaps it might have been a good idea for Johnson to have postponed his vacation, considering the world was facing a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

In early March, when there were more than 50 confirmed cases of the virus in the country, the government seemed to grasp the gravity of the situation. A four-pronged plan to “Contain, Delay, Research, [and] Mitigate” was released, and Johnson told the country: “We have all got to be clear, this is the worst public health crisis for a generation,” adding that “many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time.” Despite these alarming words, no lockdown measures were announced; instead, the country was reminded about the importance of hand washing. With these sentiments, the government appeared to be taking a herd immunity stance; this was confirmed the following day, when Sir Patrick Vallance, England’s Chief Scientific Adviser told Radio 4’s Today Programme: “Our aim is to try and reduce the peak, broaden the peak, not suppress it completely; also because the vast majority of people get a mild illness, to build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission.” That same day on a phone call, Johnson allegedly told Italy’s Prime Minister, Giuseppe Conte, that the U.K. was taking a herd immunity strategy, according to a Channel 4 documentary. In spite of all the evidence to the contrary, Downing Street has consistently denied pursuing a herd immunity strategy to defeat the virus. In order to truly achieve herd immunity, experts speculate that nearly 90 percent of a given population must have some form of immunity against the virus; without a vaccine, this means that nearly 60 million people across the U.K. would have to contract the virus, and, to date, it hasn’t been conclusively proven that contracting coronavirus provides long-term immunity against it. Scientists at Imperial College London projected that pursuing a herd-immunity strategy could have led to 250,000 deaths across the country.

Like the U.S., the U.K. suffered a limited capacity for testing in the early days of the outbreak. This impeded contact tracing and isolation for exposed individuals. Despite being one of the first countries to develop a reliable test for the virus in early February — and boasting about it — the government was slow to engage the country’s commercial testing and diagnostics sector. Doris-Ann Williams, Chief Executive of the British In Vitro Diagnostics Association, responsible for the majority of the sector in the U.K., told The Times that it wasn’t until April that the government asked for assistance. Had they liaised earlier, testing could have kept pace with the number of infections, many more people could have been tested throughout February and March, contact tracing could have been applied, and the U.K.’s active coronavirus cases could have been under significantly more control by the end of March.

Similarly, there was a failure in the procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE). At the beginning of the outbreak, the U.K.’s pandemic stockpiles did not include gowns, visors, or swabs, according to a BBC Panorama investigation. The government had arranged “just in time” contracts that were intended to fill gaps in the stockpile, if or when needed, however, many of the suppliers were Chinese manufacturers who were already strained from Chinese demand. Local suppliers, like the British Healthcare Trades Association, offered to assist the government in February by supplying PPE — but it wasn’t until April that the government accepted this offer. And, as of April 22, some British companies who had offered to help had not yet received a response. Interflex Manufacturing, for example, which supplies components to carmakers, offered to make PPE for the government’s coronavirus response; but when the company did not hear back, it began selling millions of masks, visors, and aprons to care homes across Europe instead.

Because of this failure to respond, and failure to enact contracts to provide PPE in a timely manner, the country experienced widespread shortages. The government downgraded guidelines, telling NHS staff that they would be safe wearing aprons and surgical masks rather than the surgical gowns, respirator masks and visors that had been standard issue since 2019. Public Health England even adjusted recommendations that would allow for re-use of single-use protective equipment, including masks, putting health care workers at greater risk. The government even made a questionable announcement in late April when they declared that 12 million items of PPE had been delivered to NHS trusts across the country. The BBC’s Panorama investigation uncovered that this figure was inflated, counting individual gloves towards this total, rather than counting pairs of gloves as a single unit. Paper towel and detergent — items not typically considered to be PPE — were also included within the total. Because of these shortcomings, across the country more than 200 health workers have died from contracting the virus, according to a Guardian report. Had adequate PPE been available, many of these deaths could have been prevented.

Similarly, 131 social care workers’ lives could have been saved had adequate PPE been available in care homes — although a lack of PPE was far from the only issue that these homes faced. In fact, care homes seem to have been a microcosm for the government’s bad policy decisions. Similar to the guidance in late January that the risk to the U.K. public was low, in late February Public Health England said that it was “very unlikely” that care homes would become infected, and offered no additional advice; this was based on an assumption that the U.K. would not see community transmission of the virus. However, two weeks earlier, the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies said: “it is a realistic probability that there is already sustained transmission in the UK.” Public Health England updated their guidance on March 13, suggesting that care homes review their visitation policies, encouraging those who are unwell to stay away; but, by this point, there had been 14 deaths and outbreaks in 30 care homes across the country.

Care homes were also provided with mixed guidance on the release of patients from hospitals and the need for testing; beginning in mid-March, patients were rapidly discharged from hospitals to care homes in order to free up beds for coronavirus patients, and, until mid-April, the advice from the government was: “Negative tests are not required prior to transfers/admissions into care homes.” This advice, combined with the reluctance to limit visitations, are two elements of the perfect storm that led to between 16,000 and 22,000 coronavirus related deaths among care home residents, as of mid-June; this accounts for at least a third of the country’s death toll. Had the U.K. acted decisively in January and February by stockpiling supplies and implementing lockdown measures, many of the U.K.’s 300,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 43,000 deaths could have been averted.

Brazil

Brazil’s controversial leader, Jair Bolsonaro, believes the coronavirus is merely a “little flu,” despite his country having the second highest caseload globally. According to a recent editorial in the Lancet, this is one reason that he is Brazil’s biggest threat to successfully tackling the deadly virus.

Like Trump and Johnson, Bolsonaro downplayed the severity of the pandemic; he also refused to implement a nation-wide lockdown. Although his Ministry of Health set in place mitigation measures in mid-March — closing the border with Venezuela, canceling cruises, canceling large events, encouraging social distancing, and urging travelers to self-isolate — Bolsonaro sought to quelch these measures. His cabinet put pressure on the Ministry of Health to roll them back, and, almost overnight, cruises and large events were back on, and travelers were no longer required to self-isolate. Bolsonaro even encouraged Brazilians to defy health guidelines, criticizing state governors who implemented lockdown measures. On Easter weekend he proclaimed: “No one will hinder my right to come and go,” flouting his health ministry’s stay-at-home recommendation. Based on a Reuters analysis of Google’s mobility data for the month of April, which collates cell phone movement and compares it with pre-pandemic benchmarks, Bolsonaro’s statements correlated with Brazilians carrying on with their daily routines, enabling a much wider, continuous spread of the virus. This was in stark contrast to European citizens’ movements, who were under lockdown, limiting the spread of the virus.

Throughout the pandemic, Brazil’s Health Minister, Luiz Henrique Mandetta, advocated for social distancing measures;Bolsonaro fired him in mid-April for failing to toe the party line. Mandetta was replaced by Nelson Teich, an oncologist and healthcare entrepreneur, but the sudden transition led to delays in testing and orders of new equipment, which significantly hampered the country’s ability to contain the virus.

Like his much-admired ally Trump, Bolsonaro began promoting chloroquine to treat COVID-19. However, following the results from a small study in the northwestern city of Manaus, where eleven coronavirus patients on a high dose of chloroquine died, Minister Teich refused to promote the drug. Instead, he resigned less than a month after taking the job. His position has since been filled by Eduardo Pazuello, an active-duty Army general with no medical background. Unsurprisingly, the health ministry is now actively promoting the use of chloroquine to treat COVID-19, undoubtedly endangering the lives of Brazilians.

Bolsonaro’s reluctance to implement lockdown and social distancing measures allowed the virus to spread rampantly throughout the country, wreaking havoc in vulnerable favelas and remote indigenous groups that were ill-prepared to manage the virus. Many are disillusioned with the country’s leadership, and Bolsonaro’s approval ratings have plummeted; across the country, Brazilians now bang pots and pans in protest during presidential announcements in. But as the population pushes back, so too does the administration. On June 5, the government shut down the website that released official statistics on rates of COVID-19 in Brazil, claiming the numbers had been misleading. As of this article’s writing, the Brazil’s publication of official COVID-19 statistics is still halted, leaving millions of Brazilians in the dark without accurate information about the pandemic.

Madagascar

Madagascar is somewhat of a wildcard in the world of bad pandemic policies. The coronavirus was slower to reach many countries in Africa, and as of the time of writing there were only 1,724 cases and 15 recorded deaths in Madagascar. But the country’s 45-year-old president, Andry Rajoelina, took what can only be described as an unorthodox attempt to combat the virus.

Rajoelina launched a “cure” for coronavirus — a drink called “Covid-Organics” — brewed by the state-owned Malagasy Institute of Applied Research (IMRA). Made from herbs indigenous to Madagascar, including Artemesia Annua, a plant used to help treat malaria, the drink is said to prevent and cure COVID-19. To date, no clinical trials have been conducted; instead, a “study” of 20 people was conducted over a period of three weeks. From this, the institute claims two people who had previously tested positive for the virus had been cured. In May, the president told France24: “We have 171 cases, including 105 cured. The patients who were cured took only the Covid-Organics medication.” While it’s impossible to know if these claims are true, the estimated recovery rate from COVID-19 is between 97 and 99 percent, according to WebMD, which throws the beverage’s curative powers into question.

Regardless of the veracity of these claims, the drink has been donated domestically and internationally to help slow the spread of the virus. Within Madagascar, thousands of bottles have been provided to town squares and schools, where people are encouraged to drink it twice daily for a week; internationally it has been shipped throughout Africa, and the IMRA is preparing to market the beverage for US$0.40 per bottle.

In response to increasing demand for Covid-Organics, the WHO issued a warning against untested remedies, saying that while it welcomes innovation, including traditional medicines and new therapies to treat COVID-19, “Africans deserve to use medicines tested to the same standards as people in the rest of the world.” President Rajoelina did not take kindly to this, dismissing the warning as loaded with racist and prejudiced undertones: “If it weren’t Madagascar, but a European country that had discovered the remedy Covid-Organics, would there be so many doubts? I do not think so,” he told France24.

The WHO and Rajoelina have since come to an agreement — Covid-Organics will now be part of the WHO’s fast-track clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments. In an ideal world, the beverage will show promise for combating the disease; however, the head of WHO in Africa, Matshidiso Moeti, is concerned: “touting this product as a preventative measure might then make people feel safe,” but this false sense of security could lead to riskier behaviour, which could ultimately lead to a higher caseload and death toll.

Across the world, countries have made bad decisions when attempting to tackle COVID-19. While some of this is to be expected, some of it could have been – and was – easily predicted. Some blunders were common across countries: many were slow to react; many failed to acquire the necessary supplies for protection of healthcare workers and widescale testing; many failed to assess the scale of their caseloads. Others were more unique: injecting bleach; treating the virus with an unproven herbal drink. And some countries, like Brazil, did very little, aiming to prioritize the health of their economy at the expense of their citizens’ health. While it would be impossible to include all of the bad pandemic policies from around the globe, or even from these five countries, one can hope that by exposing these cardinal sins, they can be avoided in future waves of COVID-19 and any other infectious diseases we encounter in our lifetime.